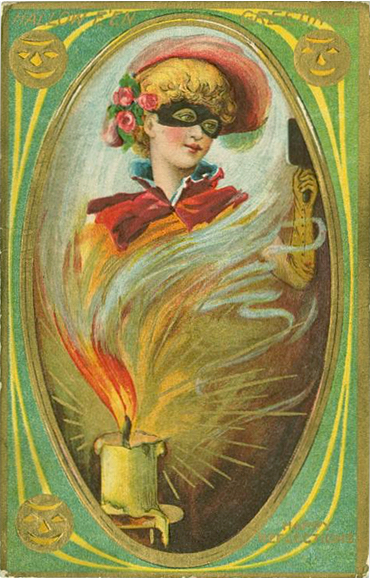

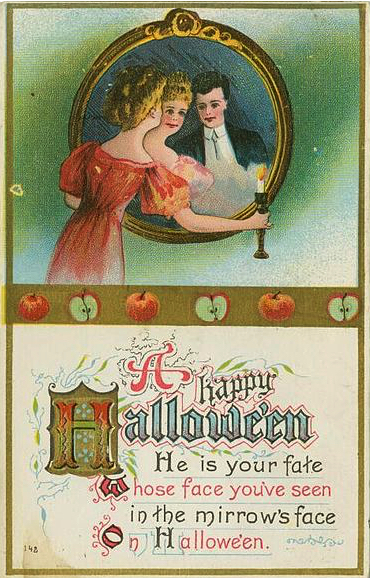

A few years ago, while combing through images of Victorian to Edwardian-era Halloween postcards, I stumbled across a repeated image that piqued my curiosity: a young woman with a candle in one hand and a mirror in the other, gazing at a man’s face where her reflection ought to be. There were variations on the theme, some romantic with saccharine rhymes about finding true love, some mocking with imps, ghosts, or lecherous old men peering out from the glass. They stood out against the expected beribboned black kittens, dancing jack-o’-lanterns, pin-up witches, and other standard spooks of contemporary Halloween imagery. I did a little digging, and stumbled across a rich history of Halloween divination games and spells.

Halloween Studies 101

Halloween has a long and constantly evolving history. It arguably blends pagan, Christian, and secular imagery more than any other major holiday. Divination plays a surprisingly significant role in that history. Once upon a long time, stretching far after the middle ages when three Catholic festivals of All Hallow’s Eve, All Saint’s Day, and All Soul’s Day replaced the Celtic harvest festival Samhain (pronounced “sow-in” and meaning “summer’s end”), divination games and spells were as much a part of traditional Halloween celebrations as trick-or-treating is today.

We don’t know exactly how old these practices are. Most of the games I read about seem to originate from rural Ireland and Scotland, although variations have also been documented in England, Wales, and the Isle of Man. (You find fewer accounts of these rituals in England. The most popular secular customs associated with Halloween bopped over to Bonfire Night in Britain after the Protestant Reformation, while the more religious customs transformed or died out, as All Hallow’s Eve was a Catholic holiday.) Most authors on the topic cite the iconic Scottish poet, Robert Burns’ 1785 poem, Halloween as one of their earliest references. We can guess these divination customs were already traditional by the late eighteenth century. Some stayed in practice, evolved into Victorian parlor games, and were carried over to the US and Canada when Scottish and Irish immigrants brought Halloween with them to the New World. Descriptions of divinatory party games can be found in North American books and magazines as late as the 1940s, although they passed out of favor by the golden age of Trick-or-Treating in the post-WWII suburban boom.

Given the season’s associations with death and horror, we might expect Halloween divinations to predict death and disaster, and in some cases they did. More games by far, however, focussed on love, luck, and marriage. Imagine being a kid on a farm in the sticks hundreds of years ago. Marriage was one of the biggest looming life events for young people in rural Ireland, Scotland, and Britain, and courtship was restricted by opportunity and custom. Holiday celebrations and gatherings provided outlets for single young people to mix, play at matchmaking, and question potential suitors. Romantic fortune-telling rituals were once a common feature of multiple holidays and Saint’s days year round. Over time, they became associated more and more with Halloween, perhaps because it was more raucous and youth-centered than other festivals, perhaps because its pagan roots peek above the soil more than other holidays’, and perhaps just a bit because marriage is scary, and, at least to the subconscious mind, sex and death go together like rama-lama-lama-da-ding-da-dee-ding-dee-dong. (Of course, I’m speculating there.)

Considered all together, the games and spells I read about seem to sort themselves into two rough categories. The first group involves domestic and comparatively secular harvest games based on associations between seasonal imagery and aspects of fortune or character. The second group involves rituals and spells based on beliefs overlapping with faerie folklore, which tend to be a bit wilder, and at times darker. It’s largely the first group, the harvest games, that evolved into Victorian parlor games and lingered into the twentieth century, while the latter group seems to have made great fodder for cautionary tales and fireside horror stories. Modern diviners and magicians might think of group A as being more in the vein of sympathetic magic, and group B as being more in the vein of conjuring or invocation.

We don’t know exactly how old these practices are. Most of the games I read about seem to originate from rural Ireland and Scotland, although variations have also been documented in England, Wales, and the Isle of Man. (You find fewer accounts of these rituals in England. The most popular secular customs associated with Halloween bopped over to Bonfire Night in Britain after the Protestant Reformation, while the more religious customs transformed or died out, as All Hallow’s Eve was a Catholic holiday.) Most authors on the topic cite the iconic Scottish poet, Robert Burns’ 1785 poem, Halloween as one of their earliest references. We can guess these divination customs were already traditional by the late eighteenth century. Some stayed in practice, evolved into Victorian parlor games, and were carried over to the US and Canada when Scottish and Irish immigrants brought Halloween with them to the New World. Descriptions of divinatory party games can be found in North American books and magazines as late as the 1940s, although they passed out of favor by the golden age of Trick-or-Treating in the post-WWII suburban boom.

Given the season’s associations with death and horror, we might expect Halloween divinations to predict death and disaster, and in some cases they did. More games by far, however, focussed on love, luck, and marriage. Imagine being a kid on a farm in the sticks hundreds of years ago. Marriage was one of the biggest looming life events for young people in rural Ireland, Scotland, and Britain, and courtship was restricted by opportunity and custom. Holiday celebrations and gatherings provided outlets for single young people to mix, play at matchmaking, and question potential suitors. Romantic fortune-telling rituals were once a common feature of multiple holidays and Saint’s days year round. Over time, they became associated more and more with Halloween, perhaps because it was more raucous and youth-centered than other festivals, perhaps because its pagan roots peek above the soil more than other holidays’, and perhaps just a bit because marriage is scary, and, at least to the subconscious mind, sex and death go together like rama-lama-lama-da-ding-da-dee-ding-dee-dong. (Of course, I’m speculating there.)

Considered all together, the games and spells I read about seem to sort themselves into two rough categories. The first group involves domestic and comparatively secular harvest games based on associations between seasonal imagery and aspects of fortune or character. The second group involves rituals and spells based on beliefs overlapping with faerie folklore, which tend to be a bit wilder, and at times darker. It’s largely the first group, the harvest games, that evolved into Victorian parlor games and lingered into the twentieth century, while the latter group seems to have made great fodder for cautionary tales and fireside horror stories. Modern diviners and magicians might think of group A as being more in the vein of sympathetic magic, and group B as being more in the vein of conjuring or invocation.

Harvest Games

Apple Paring: Skin an apple slowly with a paring knife to create a single, long peel. Throw the peel over your left shoulder and read its shape on the ground to learn your future love’s initial.

[I wouldn’t be surprised if variations on this one are still alive today. I’d always heard that it’s good luck to peel a whole apple in a single, unbroken spiral, and one of my old college friends taught me a similar kids’ game, where you twist an apple stem while reciting the alphabet. The letter spoken as the stem breaks off will be the first letter of your husband or wife’s first name.]

Apple Seed Numerology: Cut an apple in half and divine by the number of seeds visible.

[I wouldn’t be surprised if variations on this one are still alive today. I’d always heard that it’s good luck to peel a whole apple in a single, unbroken spiral, and one of my old college friends taught me a similar kids’ game, where you twist an apple stem while reciting the alphabet. The letter spoken as the stem breaks off will be the first letter of your husband or wife’s first name.]

Apple Seed Numerology: Cut an apple in half and divine by the number of seeds visible.

| Kaling: Walk blindfolded, backwards, into a vegetable patch and pull a kale stalk from the ground. Bring it home and read the size, shape, and taste to discover the nature of your future spouse. Is it shriveled, old, and bitter, or rich and sweet? Hang your kale stalk over the door. The first eligible young person to pass beneath it will become the one you marry. Oat Pulling: Blindfolded in an oat field, pull up three oat stalks. If the third stalk has no grain left, the lady of the couple in question will not be a virgin when she marries. Nut Burning: Name two nuts for yourself and a suitor, or for two lovers you know, and throw them into a fire together. The way they burn predicts compatibility. If they fly apart, the relationship will end soon. If they burn out slowly side by side, the match will last. Nut Boating: Make little boats out of walnut shells and small candles, placed in a tub of water. Name each shell for someone you know, light the candles, and watch how the boats drift together and apart. Walnut boats that drift together indicate good matches. Walnut Charms: Place little charms and trinkets into emptied walnut shells. Tie the halves back together and hand them out to your Halloween party guests. Read fortunes by the symbolism of each token. Matching charms foretell marriage. | These glowing nuts are emblems true |

Luggie Bowls: Luggie bowls are little handled bowls made of wood, ceramic, or metal. Take three small bowls. Fill one with clean water, one with dirty water, and keep one empty. Taking turns, have your blindfolded party guests dip their fingers in one bowl each. Those who choose the bowl of clean water can expect clean and pure spouses. Those who get the dirty water will may marry widows and widowers, or else find their partners anything but clean and pure by the wedding day. Those who pick the empty bowls won’t be getting married at all, at least not anytime soon.

Have Your Cake and Read it Too: Bake fortune-telling tokens into a cake. A key for travel, a ring for marriage, a coin for wealth, and a thimble for spinsterhood. Whoever gets the token in their slice of cake can expect its accompanying fortune.

This was often done, and still is today, with barmbrack, a traditional Irish cake made with black tea, dried fruit, and spices. (Check out this follow-up post with a modern American take on this one.)

Sweet Dreams: Place a sprig of rosemary or a slice of apple caught while apple bobbing under your pillow on Halloween night to invoke prophetic dreams of your intended.

Witches, Faeries, Ghosts, and Wraiths

To understand this next group of customs, you need to know a little about traditional Scottish and Irish folklore. Alongside the Christian God and Devil, Celtic beliefs in faeries and spirits whose world overlaps with our own persisted. Many believed that the boundary between our world and this spirit world thinned during this time of year, and that malevolent critters could cross into our terrain on Halloween night and run amok. “Faeries” here weren’t the cutesy wee ladies with butterfly wings we think of today, flitting through garden parties and granting pleasant wishes. That image is a sanitized and trivialized Victorian invention. These were wild beings, uncanny little people, and otherworldly beasties with their own agendas and moral codes. They could be friendly or they could be deadly; some were both. Halloween was a night for ghosts, faeries, and witches to roam and wreak havoc, and a night for deceased loved ones, friends, relatives, and neighbors, to revisit their old homes. All things wicked and trickstery might be kept at bay with bonfires, candles, prayers, and the ringing of consecrated bells, while offerings of food, drink, and a fire on the hearth might be left overnight for spectral friends.

In addition to ghosts, spirits, and faeries, people believed that part of a living person’s spirit could separate from the body, travel, and even be spotted by others, like a ghost. This part of the spirit was called the “wraith” in Scotland, or the “fetch” in Ireland. 364 Days out of the year, sighting a living person’s ghost would portend their body’s immanent death, but on Halloween it was said the fetch could appear to a future spouse. People played all kinds of tricks in attempts to conjure glimpses of their intendeds, even resorting at times to calling on the devil. As Wiliam Aiton (b. 1760 - d. 1847), a Scottish lawyer and agriculturalist once wrote, “Many of the lower orders, in that country still believe the devil is ready at their call, and on their using certain capers and spells to discover a secret which generally occupies much of their thought; namely, who is to be their future spouse.” (2)

In addition to ghosts, spirits, and faeries, people believed that part of a living person’s spirit could separate from the body, travel, and even be spotted by others, like a ghost. This part of the spirit was called the “wraith” in Scotland, or the “fetch” in Ireland. 364 Days out of the year, sighting a living person’s ghost would portend their body’s immanent death, but on Halloween it was said the fetch could appear to a future spouse. People played all kinds of tricks in attempts to conjure glimpses of their intendeds, even resorting at times to calling on the devil. As Wiliam Aiton (b. 1760 - d. 1847), a Scottish lawyer and agriculturalist once wrote, “Many of the lower orders, in that country still believe the devil is ready at their call, and on their using certain capers and spells to discover a secret which generally occupies much of their thought; namely, who is to be their future spouse.” (2)

Summoning The Fetch

Apple, Candle, and Mirror: At midnight on Halloween night, sit in front of a mirror with an apple, a candle, and a knife. Light the candle. Cut the apple into nine pieces with the knife. Eat all but the last slice, one by one. Your future spouse will appear in the mirror to claim the last bite.

Ring Around the Barley: Run blindfolded, counter-clockwise (“widdershins”), three times around a large stack of barley. At the last turn’s end, you’ll run into the arms of your intended.

Dumb Cake: With a group of single friends, mix and bake a cake together in total silence. When the cake is finished, your future husbands should appear to claim a slice.

Blue Clew: Take a blue ball of yarn and, holding the loose end, throw the ball into a lime kiln, or out the window at midnight on Halloween. When you feel a tug on the string, ask who holds the clew. The voice of your spouse to be will answer.

Hemp Sewing: Walk through a hemp field, sowing seeds behind you and calling for your love to follow after. You beloved will appear behind you.

Sleeve-Dipping: Dip your sleeve into pond or well water, hang your shirt to dry by the fire, and go to bed. Your future spouse will appear in the night to turn the shirt over so it will dry on both sides.

According to Robert Burns, you should soak your sleeve “whare three lairds’ lands meet at a burn.” (3) (Translation: a body of freshwater on the interesting boundaries of three owners’ lands.) According to another story, the water should come “from a well which brides and burials pass over.” (4)

Turning the Silverware: Set places at your dining room table. At midnight, turn all the silverware upside-down. Your beloved will arrive to turn the place settings back as they should be.

Ring Around the Barley: Run blindfolded, counter-clockwise (“widdershins”), three times around a large stack of barley. At the last turn’s end, you’ll run into the arms of your intended.

Dumb Cake: With a group of single friends, mix and bake a cake together in total silence. When the cake is finished, your future husbands should appear to claim a slice.

Blue Clew: Take a blue ball of yarn and, holding the loose end, throw the ball into a lime kiln, or out the window at midnight on Halloween. When you feel a tug on the string, ask who holds the clew. The voice of your spouse to be will answer.

Hemp Sewing: Walk through a hemp field, sowing seeds behind you and calling for your love to follow after. You beloved will appear behind you.

Sleeve-Dipping: Dip your sleeve into pond or well water, hang your shirt to dry by the fire, and go to bed. Your future spouse will appear in the night to turn the shirt over so it will dry on both sides.

According to Robert Burns, you should soak your sleeve “whare three lairds’ lands meet at a burn.” (3) (Translation: a body of freshwater on the interesting boundaries of three owners’ lands.) According to another story, the water should come “from a well which brides and burials pass over.” (4)

Turning the Silverware: Set places at your dining room table. At midnight, turn all the silverware upside-down. Your beloved will arrive to turn the place settings back as they should be.

License to Witch?

Not surprisingly, Halloween fun was typically gendered. While the boys roamed out for a night of pranking and vandalism, wreaking vengeance on cantankerous neighbors and hounding rumored witches, the girls stayed in on the farm, playing parlor games or sneaking to the barn or cellar for a romantic dalliance with the witch’s craft.

These conjuring spells laid fertile ground for pranks and flirtations. There’s little to stop an interested suitor from hiding beneath a young lady’s window to catch her ball of yarn and call his own name, body, soul, fetch and all. There’s little to stop a practical joker from hiding in the lime kiln or behind the mirror to whisper the name of a drunkard, boor, or devil. Many accounts I read of these practices came accompanied by campy horror stories of young ladies getting frightened to death by what they saw in the mirror, or frightening themselves away from divination for life after suffering a well-executed prank. There’s a sense of humor to all these games, spooky or tame. Robert Burns’ poem is full of instances where fortune-seekers find themselves the butt of a joke, or else find bawdy ways to take control of their own fates in oat fields and atop hay stacks. That said, the jokes and tales veer a bit more cautionary with this second grouping. Tossing an apple peel over your shoulder is one thing. Summoning spirits in the devil’s name is another, even if those spirits are still attached to living people. In at least one case, a Scottish woman was investigated and sentenced “a rebuke before the congregation” for performing a Halloween sleeve-dipping charm. (4)

It’s worth noting, however, that all these little rituals were kept alive, and for the most part tolerated, by Christian populations. (Catholicism dominated in Ireland; the Church of England dominated in England, Wales, and the Isle of Man; Presbyterianism and the Church of Scotland mingled with some Catholicism in Scotland.) These divination games weren’t necessarily Pagan or witchcraft practices the way some might think of them today. Rather, they were folk practices, superstitions, and entertainments that evolved in Christian cultures with pagan roots, and that drew on imagery from secular, Christian, and folkloric sources, each to different degrees.

Westerners have long held space for popular customs and superstitions that, while arguably magical in nature, fall outside the historically reviled realm of witchcraft practices. Additional license for rituals that pushed that line seems to have been granted on Halloween, with its transgressive and supernatural themes. If someone put on a mask and cavorted around town year round, they’d be declared insane, but it was expected for masked performers to beg for cakes and money in exchange for a song or dance on Halloween. If a young boy stole cabbages from farmers’ fields, threw stones at windows, and unhinged gates and barn doors every day, he’d be punished as a thief and a vandal, but if he did all the above and more on Halloween night, it’d be brushed off as child’s play, and he might get a slap on the wrist at worst - if he was caught. If a young lady was thought to hold a permanent contract with the Devil in exchange for supernatural powers that she used for personal gain and to inflict harm out of spite, she’d be called a witch and persecuted accordingly. But if a young lady got caught dipping her sleeve in the black pond by the crossroads at midnight on Halloween, she might have gotten whooped by Grandma or chastised at church, but she probably wouldn’t have been ostracized or burnt at the stake.

This doesn’t mean, however, that Halloween granted one an open license to practice witchcraft. On the contrary, it usually gave young men license to torment, threaten, and vandalize suspected witches, who were likelier than not ornery but harmless older women. When these practices were most popular, witches were still very much feared as malevolent and dangerous people. It’s unlikely that a young woman at the time would have considered slicing an apple before her mirror or turning over the silverware as witchcraft, nor would she identify herself as a witch for doing so.

These conjuring spells laid fertile ground for pranks and flirtations. There’s little to stop an interested suitor from hiding beneath a young lady’s window to catch her ball of yarn and call his own name, body, soul, fetch and all. There’s little to stop a practical joker from hiding in the lime kiln or behind the mirror to whisper the name of a drunkard, boor, or devil. Many accounts I read of these practices came accompanied by campy horror stories of young ladies getting frightened to death by what they saw in the mirror, or frightening themselves away from divination for life after suffering a well-executed prank. There’s a sense of humor to all these games, spooky or tame. Robert Burns’ poem is full of instances where fortune-seekers find themselves the butt of a joke, or else find bawdy ways to take control of their own fates in oat fields and atop hay stacks. That said, the jokes and tales veer a bit more cautionary with this second grouping. Tossing an apple peel over your shoulder is one thing. Summoning spirits in the devil’s name is another, even if those spirits are still attached to living people. In at least one case, a Scottish woman was investigated and sentenced “a rebuke before the congregation” for performing a Halloween sleeve-dipping charm. (4)

It’s worth noting, however, that all these little rituals were kept alive, and for the most part tolerated, by Christian populations. (Catholicism dominated in Ireland; the Church of England dominated in England, Wales, and the Isle of Man; Presbyterianism and the Church of Scotland mingled with some Catholicism in Scotland.) These divination games weren’t necessarily Pagan or witchcraft practices the way some might think of them today. Rather, they were folk practices, superstitions, and entertainments that evolved in Christian cultures with pagan roots, and that drew on imagery from secular, Christian, and folkloric sources, each to different degrees.

Westerners have long held space for popular customs and superstitions that, while arguably magical in nature, fall outside the historically reviled realm of witchcraft practices. Additional license for rituals that pushed that line seems to have been granted on Halloween, with its transgressive and supernatural themes. If someone put on a mask and cavorted around town year round, they’d be declared insane, but it was expected for masked performers to beg for cakes and money in exchange for a song or dance on Halloween. If a young boy stole cabbages from farmers’ fields, threw stones at windows, and unhinged gates and barn doors every day, he’d be punished as a thief and a vandal, but if he did all the above and more on Halloween night, it’d be brushed off as child’s play, and he might get a slap on the wrist at worst - if he was caught. If a young lady was thought to hold a permanent contract with the Devil in exchange for supernatural powers that she used for personal gain and to inflict harm out of spite, she’d be called a witch and persecuted accordingly. But if a young lady got caught dipping her sleeve in the black pond by the crossroads at midnight on Halloween, she might have gotten whooped by Grandma or chastised at church, but she probably wouldn’t have been ostracized or burnt at the stake.

This doesn’t mean, however, that Halloween granted one an open license to practice witchcraft. On the contrary, it usually gave young men license to torment, threaten, and vandalize suspected witches, who were likelier than not ornery but harmless older women. When these practices were most popular, witches were still very much feared as malevolent and dangerous people. It’s unlikely that a young woman at the time would have considered slicing an apple before her mirror or turning over the silverware as witchcraft, nor would she identify herself as a witch for doing so.

Adaptations

I wrote this article for fun and entertainment, from a love of folklore and historical curiosities. I wrote the ritual descriptions in the style of directions for rhythm, and to make them more immediately imaginable. To those reading with a desire to rekindle old traditions and expand their divination or witchcraft repertoires, I have just a few words of advice:

The games and spells I’ve described above have already shifted and changed over the years, and have scores of variations. You can make up your own variations. These obviously correspond to antiquated models of courtship, sexuality, gender, marriage, and family, so for a lot of us they automatically work better as inspiration than as recipes. Let them inspire or entertain you as you like. Stay safe, stay sensible, and remember: just cause it’s old doesn’t mean you keep it.

Check out the Halloween history books I read (listed in the sources below) for more info on these and other Halloween rituals.

The games and spells I’ve described above have already shifted and changed over the years, and have scores of variations. You can make up your own variations. These obviously correspond to antiquated models of courtship, sexuality, gender, marriage, and family, so for a lot of us they automatically work better as inspiration than as recipes. Let them inspire or entertain you as you like. Stay safe, stay sensible, and remember: just cause it’s old doesn’t mean you keep it.

Check out the Halloween history books I read (listed in the sources below) for more info on these and other Halloween rituals.

Citations

(1) On Nuts Burning, Allhallows Eve by Charles Graydon, 1801. Quoted by David J. Skal, Death Makes a Holiday, pp.26-27.

(2) William Aiton quoted by Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, p.43.

(3) Robert Burns quoted by Lisa Morton, Trick or Treat, p. 42.

(4) Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, A Historical Account of the Belief in Witchcraft in Scotland (London, 1884), p.97. Quoted by Lisa Morton, Trick or Treat, p. 43

(2) William Aiton quoted by Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, p.43.

(3) Robert Burns quoted by Lisa Morton, Trick or Treat, p. 42.

(4) Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, A Historical Account of the Belief in Witchcraft in Scotland (London, 1884), p.97. Quoted by Lisa Morton, Trick or Treat, p. 43

Sources

PRINT

Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books, 2012.

Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Skal, David J. Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. Bloomsbury, 2002.

WEB

Burns, Robert. “Halloween.” Burns Country: Complete Works: Halloween, www.robertburns.org/works/74.shtml. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Burns, Robert. “Halloween (Translation Into Modern English).” Myth For Kids, www.mythicjourneys.org/mythkids_oct06_burns.html. Accessed Oct. 2016

Galindo, Brian. “13 Odd and Disturbing Vintage Halloween Postcards.” Buzzfeed, 10 Oct. 2013, www.buzzfeed.com/briangalindo/13-odd-and-disturbing-vintage-halloween-postcards?utm_term=.as4PrZnrr#.ktjgGE1GG.

Wang, Angela Meiquang. “22 Truly Bizarre Vintage Halloween Postcards.” Buzzfeed, 19 Oct. 2012, www.buzzfeed.com/angelameiquan/21-bizarre-vintage-halloween-postcards-70fn.

IMAGES

A Happy Hallowe’en. Date unknown. New York Public Library, New York. Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/32951986@N05/4055669929/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Hallowe’en Greetings. Date unknown. New York Public Library, New York. Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/32951986@N05/4056411062/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Image from page 76 of "The poetical works and letters of Robert Burns" 1869. The Library of Congress. Internet Archive Book Images, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14784810625/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Wright, J. M., and Edward Scriven. Illustration to Robert Burns’ Poem Halloween. 1841. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:J._M._Wright_-_Edward_Scriven_-_Robert_Burns_-_Halloween.JPG. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Note: I sourced all my images from Wikimedia Commons and edited them for color and clarity. They were all identified as being in the public domain with no known copyright restrictions in their countries of origin and/or the U.S.

Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books, 2012.

Rogers, Nicholas. Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Skal, David J. Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. Bloomsbury, 2002.

WEB

Burns, Robert. “Halloween.” Burns Country: Complete Works: Halloween, www.robertburns.org/works/74.shtml. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Burns, Robert. “Halloween (Translation Into Modern English).” Myth For Kids, www.mythicjourneys.org/mythkids_oct06_burns.html. Accessed Oct. 2016

Galindo, Brian. “13 Odd and Disturbing Vintage Halloween Postcards.” Buzzfeed, 10 Oct. 2013, www.buzzfeed.com/briangalindo/13-odd-and-disturbing-vintage-halloween-postcards?utm_term=.as4PrZnrr#.ktjgGE1GG.

Wang, Angela Meiquang. “22 Truly Bizarre Vintage Halloween Postcards.” Buzzfeed, 19 Oct. 2012, www.buzzfeed.com/angelameiquan/21-bizarre-vintage-halloween-postcards-70fn.

IMAGES

A Happy Hallowe’en. Date unknown. New York Public Library, New York. Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/32951986@N05/4055669929/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Hallowe’en Greetings. Date unknown. New York Public Library, New York. Flickr, www.flickr.com/photos/32951986@N05/4056411062/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Image from page 76 of "The poetical works and letters of Robert Burns" 1869. The Library of Congress. Internet Archive Book Images, Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14784810625/. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Wright, J. M., and Edward Scriven. Illustration to Robert Burns’ Poem Halloween. 1841. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:J._M._Wright_-_Edward_Scriven_-_Robert_Burns_-_Halloween.JPG. Accessed Oct. 2016.

Note: I sourced all my images from Wikimedia Commons and edited them for color and clarity. They were all identified as being in the public domain with no known copyright restrictions in their countries of origin and/or the U.S.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed